This post is about my story in Long Hidden, so I’ll begin it with a plug: Long Hidden is out and available for purchase. You can get it on Amazon in paperback, for Kindle, and for Nook. Please, please take a moment to support this amazing anthology and these amazing works of fiction.

I’m sure we’ve all read Junot Diaz’ MFA vs POC article to death by now. In it, he talks about how his MFA experience at Cornell was harrowing, in large part because he was one of only a small group of PoC in a mostly white space:

In my workshop we never explored our racial identities or how they impacted our writing—at all. Never got any kind of instruction in that area—at all. Shit, in my workshop we never talked about race except on the rare occasion someone wanted to argue that “race discussions” were exactly the discussion a serious writer should not be having.

In my workshop the default subject position of reading and writing—of Literature with a capital L—was white, straight and male. This white straight male default was of course not biased in any way by its white straight maleness—no way! Race was the unfortunate condition of nonwhite people that had nothing to do with white people and as such was not a natural part of the Universal of Literature, and anyone that tried to introduce racial consciousness to the Great (White) Universal of Literature would be seen as politicizing the Pure Art and betraying the (White) Universal (no race) ideal of True Literature.

In my workshop what was defended was not the writing of people of color but the right of the white writer to write about people of color without considering the critiques of people of color.

I don’t have a MFA (I have a MPA, as a matter of fact), but my undergraduate degree is in fiction, so I know a bit about workshops. It found it amazing how, in a city with a huge population of blacks and other people of color, writing workshops could be so full of white people. I know that I probably had it better than Mr. Diaz (my poetry writing workshop had approximately 17 students in it. 7 were black. There was a Latina too, if I recall correctly–though I don’t remember her name.) but the problem with overhanging whiteness in spaces where creation happens is that said whiteness is suffocating, and oftentimes infused with this polite, mocking hostility regarding the creations of PoC that many of us are already very aware of.

In my first year workshop, there was a young dreadlocked black woman who wrote in the tradition of Hurston, Walker, and Wright. Homegirl took big steps. She wrote in a powerful voice that mixed Wright’s sensibilities with Hurston’s down-home universes. Her stories examined the unique kinship of women who love each other in all the ways that humans should. They were powerful and poignant. She wove images in her work that captured the sorrow and joy of being in love.

But her dialogue. Oh! A tragedy.

She used AAVE. Vernacular. Dialect. American black folks’ speak. That specter of language, that literary trick that made the folks in our workshop cringe in their boots with actual physical discomfort because they didn’t get it, because it was alien and they didn’t understand, or because they didn’t think it had an appropriate use in the type of high-minded literature that undergraduate students in a first year writing workshop like to think that they are producing.

I think that, for the writers in my class, they disliked homegirl’s use of her home code because all of us (the black students) could read it and understand it with ease. We didn’t have a problem with the dialogue, we understood the slang and didn’t think that the work was invalidated by the fact that the characters spoke the way that they did. Hell, it was the speech of our kinfolks–mamas and grandmamas and uncles who dropped g’s and let r’s stretch out and used slang that we brewed up in our communities until rappers and pop stars decided to introduce them to the world so that various well meaning groups (of all colors) could turn up their noses and sneer–look at that uneducated language! Look at how boorish and guttural it is! One of the older students, a Vietnam veteran, called her work “A ghetto drama”.

I think that those folks in my class were just mad that we dared have something that they couldn’t access, even something as trivial–and as powerful–as a shared language. And they refused to come out of their own places and understand how powerful that language was because they were too busy seeing it as stupid, as a joke, as something to be ridiculed or something to invalidate amazing works of writing.

I woke up this morning to my friend and writing mentor tweeting about how much he loved the prose in my story and I was touched. He is one of the best writers that I know, and to get praise from him is truly something amazing. But there was something in his tone, something defiant–I could sense the #CAPSCAPSCAPS lurking about and I dug deeper. Eventually, I came upon a review of Long Hidden written by a reviewer at Strange Horizons. Regarding my work, she says:

Troy L. Wiggins’s “A Score of Roses” features heavy use of phonetic dialect, a literary trick which works perhaps one time out of a hundred—a shame, because the story underneath all the “chil’ren”s and “yo’self”s is charming.

I was shocked. Not quite angry. I looked at it in a detached way while making my eggs, like, “sucks for that guy.”

And, to be honest, I’m still not angry at the reviewer for not understanding before that review went to print exactly why her statement would be problematic. That she was essentially claiming that the voice I used to tell my story wasn’t sufficient, because it was a trick–and hackneyed to boot. That maybe this suggestion crossed the line from “i didn’t like this story” to “this story’s quality is invalid because of this THING.” Another friend of mine, another fantastic creator, recently gave me this advice: “Tell it true.” Sure, I could have used a style of dialogue that was less–whatever, I don’t know what would have been appropriate for the reviewer–but it wouldn’t have been true.

Of course, there’s more roiling about inside of me regarding this review. I suppose I should be glad that she found my story “charming” despite my unfortunate choice of literary trickery. But I think that the conversation that sprang from this review said everything that I would have said, and much better than I could possibly say it. I’m eternally grateful to the editors of this anthology, Daniel José Older and Rose Fox, for giving PoC creators a space to show the world exactly why stories and histories such as this are so very necessary.

Please support Long Hidden by buying a copy. Tell yo’ friends!

UPDATE: I got a pingback from an editorial at Abyss & Apex Magazine wherein Wendy Delmater and Tonya Liburd discuss the use of phonetic dialect in stories. Now, keep in mind that this was more a presentation of an example that supports their decision to cut dialect in a particular work–and not an attack on the use of dialect itself. Still, there were still some parts of it that I found problematic.

The editorial begins with Wendy Delmater outlining how the use of heavy dialect might make stories inaccessible for readers:

Yesterday, while we were working on editing an A&A story containing patois, there was a genre kerfuffle and Twit storm about a Strange Horizons reviewer who complained there was too much dialect in a piece by a person of color. People lambasted the review, because, Racism. In this editorial Tonya Liburd and I want to talk about our process in allowing enough of the original flavor of our Caribbean short story “Name Calling” (next issue) without burying the story under so much inaccessible language that the tale itself could not shine through.

We wanted our readers, who span the English-speaking world, to feel as if they were transported to the Caribbean – but without constantly feeling like they needed to stop for directions. We looked to Grenadian author Tobias S. Buckell (Crystal Rain, Ragamuffin, Sly Mongoose) as an example of an author who used authentic island patois without overwhelming the story to the point where he alienated a large portion of his non-Caribbean readers.

And that’s valid. Authenticity is important, but so is clarity. These stories are for the readers, after all, and they have to understand what’s going on in them. However, this is a very, very obvious point. Delmater–who I’m addressing mostly because Liburd treads lightly in this editorial–then goes on to say:

By the way, accents overwhelming a story is not just a question of white/non-whiteness. I gave Tonya an example of white-on-white accents overwhelming a story: George MacDonald’s Alec Forbes of Howglen[…]the novel Alec Forbes of Howglen was written in what I considered an impossibly thick, but very authentic Scottish brogue. Howglen was re-released in 1985 as The Maiden’s Bequest, in which editor Michael Phillips toned down the brogue so the story could shine through. Toning down the brogue without totally removing it caused this 1800s novel, originally reviewed by Lewis Carroll, to sell and be reviewed well in this day and age. Toning down the “authentic” language made it accessible.

Would you accuse me, a woman with the maiden name of Campbell, of “racism” because she found the thick, authentic Scottish accents in the original novel obscured the story?Then let’s not complain that a reviewer felt that over-using phonetic dialect in a story was, in her opinion, a flaw.

My response to this is twofold.

1.) There are two instances of dialect pointed out in the review: “chil’ren” and “yo’self”. Is it really that much of a stretch to imagine what I might have been saying in those instances? I know that I’m a bit biased because I’m familiar with the nuances of that spoken language, but–I mean, come on. Really? Many of the people that responded to Roses after the review said that the dialect wasn’t a problem, or that it didn’t hinder their enjoyment/understanding of the story.

2.) I don’t want to throw around the “R” word here (dun dun dunnnnn), but these things don’t happen in a vacuum. Long Hidden is a Speculative Fiction anthology. In addition to southern African American dialect, I used an elven language that I made up some years ago for a RPG session. Now, while that language doesn’t play a huge part in the story, there was no mention of the use of elvish at all. And, again, Junot Diaz says it much better here (i think most of you already know this quote):

“Motherfuckers will read a book that’s one third Elvish, but put two sentences in Spanish and they [white people] think we’re taking over.

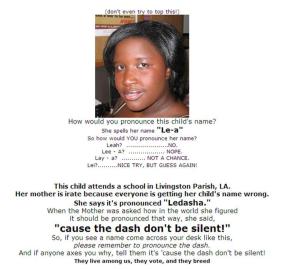

There are college courses in Klingon. You can learn to speak Sindarin on Youtube. Dothraki omniglot page? It exists. The idea that a fictional language has more legitimacy in storytelling than the actual language that I use to speak to my mother on the telephone is very, very telling. The Scottish example fails, in my opinion, because Scottish brogue hasn’t been made to represent stupidity and backwards thought all over the English speaking world. There is very little subtext: to call a Scottish brogue inaccessible means that it’s inaccessible and that people might have trouble understanding it. However, no matter how well intentioned, the delegitimizing and suggested erasure of voices like the one I used in this story has very sinister racial undertones, especially in America. It’s the same kind of thought process that undergirds memes like this:

The woman in this picture was a fellow english teacher in South Korea, and that’s not even close to her name.

(And that’s just an example of how well-meaning folks of all races view my home code. There are no rules or no sense involved. Just a bunch of mumbo jumbo. It’s so easy, anyone can create a fake Facebook account and master it.)

Now, I’m not suggesting that either of these editors would ever go this far down the rabbit hole…but, as Daniel said in the Storify, this kind of erasure and gatekeeping is detrimental to other SF/F writers of color who want to put their work into the world but fear that they will be stopped by people who think that it’s okay for a story to be written in obscure Shakespearean dialect–but consider African American dialects to be too alienating for readers.

Again and again, this situation only serves to underline the importance of supporting Long Hidden and other safe spaces for creators of color.

EDIT: Mistakenly referred to Tonya Liburd as the original reviewer. That would actually be Katherine Farmar. My mistake and apologies.

I had only heard of the anthology because Twitter blew up yesterday, and in a way I’m glad it all happened– I wasn’t familiar with your work before and the story is great. Looking forward to getting to more of the stories over the course of this week.

Thanks for reading! I’m so glad that you’re enjoying the anthology. Also glad about the hullabaloo–it made the anthology just that much more visible.

I’m trying to see the positive light in this whole situation. I think the buzz/backlash from that review has brought you more readers and bigger sales for Long Hidden.

The dialect for me didn’t seem like a trick and I wasn’t even consciously aware of it, probably because it’s a language I can speak and understand.

Keep writing.

There were some positives in the review. The reviewer rightly spotlighted the stories of Rion Amilcar Scott and Jamey Hatley…and you’re right about the buzz. All of this support is mind-boggling.

I’m glad that the dialect wasn’t a problem for you. Can you believe that that’s a toned down version? There would have been some real issues had I gone with the dialogue I had at first.

See…

My mother would say “the devil meant it for evil…”

If not for a tweet from Tanarive Due, linking to the snapping of Daniel José Older via Twitter/Storify, I might not have been introduced to the tremendous anthology that is Long Hidden. Consider it copped! Here’s to voices without compromise.

All the good things to you and your comrades.

I’m glad at the exposure, and I really hope you enjoy the anthology. There are some GREAT stories in it.

Pingback: Vernacular & Literary Tricks

Great post, Troy, and one I think should be required reading for writers (especially white writers who “don’t see race”) along with Junot Diaz’s post about his experiences.

I think language and dialect and word choices and sentence structure are all part of how a writer makes a story work, and brings characters and a world alive. Others have expressed it better than I can in the reaction to Long Hidden and the review in question, but I think Daniel said it best when he tweeted that that moment when a writer finds his/her/their voice, it is one of the most important moments in their writing life. I didn’t find the many different voices in Long Hidden jarring or hard to understand (I may well have missed important context due to my unfamiliarity with some ways of speaking or expression), but what loved about many of them, yours especially, was the way each “felt” like its own place and time and *self*. That doesn’t happen with a so-called “universal” voice; that happens when an individual voice lights it up.

You’ve hit the nail on the head, Jon. This anthology was about trumpeting the unique voices of the writers and the histories held in their stories. This was important both for the writers and for the genre.

Diminishing the uniqueness of narrative voices in a dialogue such as this seems almost antithetical.

I’m very glad you enjoyed my story and thankyouthankyou for all of your support of Long Hidden!

Pingback: Authentic Voice or Clarity? A Conversation | Abyss & Apex

Haven’t read Long yet but it is in my library and on the strength of this post alone is moving to the front of the pile. I sure hate that today we’re still doing this, fighting for out spot among the rest, to be counted as valid, to be heard in our OWN VOICES IN OUR WORDS. Keep it going T.

Pingback: Where are the songs of Trinidad? Being drowned out by ballads in Klingon… | Miss Fickle Reader

THANK you. Junot says it best, but sf has always been a genre that drops you into an unfamiliar culture and lingo and expects you to figure that shit out. Nobody talking about how they don’t understand what “droog” or “frelk” means.

Pingback: The Writer and the Critic: Episode 39 | Kirstyn McDermott

Pingback: A Score of Roses Link Roundup | Troy L. Wiggins